#52 Ancestors 2020

Week 33 - Troublemaker.

When my youngest brother was born and my parents decided to

call him Michael, my grandmother was not happy.

“Uncle Mick” (her brother in law) was a drunken no-hoper, and she

thought it was a mistake to give the new baby the same name.

Not believing that naming him Michael would doom him, my

parents went ahead. But when I began my

research into the family, I was curious about the origin of my grandmother’s

hostility to my great uncle Michael and determined to find out more.

Sadly, lots of it was true.

Michael was trouble.

Michael Garrard Gleeson was born in 1892, the second of five

children born to James Patrick and Mary Gleeson (nee Crummy.) He was born In Lismore, NSW where his father

worked for some years on the railways and then in the construction industry. With his partner Jeremiah Finn (his mother-in-law’s

third husband), James formed the company Gleeson & Finn, who were

responsible for building many of the early streets of Lismore, and three of the

reservoirs.

In about 1903, when Michael was 11, the family moved to

Brisbane. It’s not clear what they were

doing for the next few years but by 1916, my great grandfather had a new career

as a publican. He worked at a succession of Brisbane hotels, including the

famous Regatta at Toowong and the Alliance (at Spring Hill). In both of these places Michael worked as a

barman.

In 1914, when WWI broke out, Michael enlisted in the

Australian Army. He served for exactly one month before he was discharged for

health reasons – “bad elbow” was the written excuse.

In 1916, with Australia desperate for new recruits, he tried

again and was accepted. On his admission

sheet for this enlistment, he records one brush with the law – a conviction for

drunkenness*.1 He is described as being

5’6” tall with fair complexion, blue eyes and brown hair. He weighs only 133 lbs (about 52kilograms)

Michael sailed on 24 January 1917 on the troop ship

“Ayrshire”. By April he was in France

with the 15th AIF who fought on the Somme, by July he was in

trouble. His war record states that on 7

July he was charged with “hesitating to obey an order” and “violently resisting

arrest”. In September he was absent

without leave for 24 hours and had his pay docked, then he was hospitalized

with trench fever and sent back to hospital in England.

This seems to have been the end of Michael’s tour of duty –

he remained in England for several months, during which he was constantly

recorded as ‘Absent without Leave” and “Absent from Parade.” In May of 1917 he was shipped home.

Once home, Michael resumed work as a barman at his parents’

hotel. This was perhaps the worst

imaginable place for him to be.

The first newspaper report I can find is dated November

1918. Michael was charged with stealing

a sum of nine pounds and a few shillings, which was the change left on the bar

when another soldier paid for their drinks.

He then refused to give it back.

The case was reported extensively in the Brisbane papers, but in the end

the Judge concluded that all the men were drunk, and as Michael had agreed to

return the money, the case was closed.

In 1919, Michael was charged with stealing a bicycle. The policeman who brought the charge

explained to the magistrate that he would not proceed on the grounds that “the

accused was too drunk at the time of the alleged offence to be capable of knowing

what he did.” In discharging him, the magistrate said, “My advice to you is to

leave the drink alone.”

He didn’t. There is a

string of offences throughout the 1920s.

In 1921 he was charged with stealing some boots while drunk, and in 1922

with breaking into a warehouse with another man and stealing some beer and

stout. In that year, a prohibition order

was taken out against him, forbidding anyone from selling alcohol to him. In 1926, when he was arrested again for

breaking a glass shop door while under the influence, he was remanded on the

basis that he be admitted “to Dunwich”*2

According to Wikipedia, “The Dunwich Benevolent Asylum was a benevolent

asylum for the aged, infirm and

destitute operated by the Queensland Government in Australia. It was located at Dunwich on North

Stradbroke Island in Moreton

Bay and operated from 1865 to

1946."

One of the reasons for his

admission may have been evidence given of an apparent attempt on his own life

in 1921. There is a newspaper report of

him being admitted to hospital after being discovered with a wound to his

throat “recently inflicted” and with blood flowing.

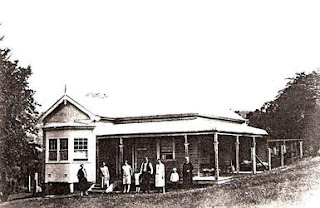

When James and Mary Gleeson bought

the freehold of the Club Hotel in Warwick, Queensland in 1926, it may have been

partly an attempt to remove Michael from Brisbane, but his problems didn’t go

away. There are a few arrests for

drunkenness through the 1930s and in 1938 a more serious attempt on his life. Again, he cut his throat, but this time

inflicted worse damage, with a razor, and was admitted to hospital in a serious

condition. The newspaper reported that

he was not living at home at this time but was found in the vicinity of his

parents’ hotel - I wonder if his parents had given up on him?

Surprisingly, Michael married in

1944, when he was 51. Nothing is known

about his wife, May Austin. Was she a

drinking companion or a positive influence in his life?

If the latter, it was really too

late. Michael died aged 54 in 1947. His death certificate records “chronic

alcoholism” as a major cause of death.

|

| Michael's grave at Lutwych cemetery in Brisbane |

I felt incredibly sad reading

the trajectory of Michael’s life through the numerous police reports on

“Trove”. While the police, and perhaps

his family, saw him as a troublemaker, he was clearly a very troubled

soul.

There are so many unanswered questions. Was his problem with alcohol already

beginning to manifest itself in 1914, when he was first arrested? Did his time in France during the War make

everything worse, or would it all have happened anyway? Was there something in his childhood or his

family relationships which sowed the seed?

There is no one left to ask.

*1October 1914.

Charged 5 shillings or 6 hours in the lock up.

*2 see clipping